Battleship: Difference between revisions

imported>Robert A. Estremo (→The underwater threat: add image) |

imported>Robert A. Estremo m (→Aircraft versus battleships: formatting) |

||

| Line 112: | Line 112: | ||

| publisher = U.S. Naval Historical Center}}</ref> | | publisher = U.S. Naval Historical Center}}</ref> | ||

The [[USS Oklahoma|'' | The [[USS Oklahoma|USS ''Oklahoma'']] later sank while being salvaged. All the other battleships at Pearl Harbor were damaged, but eventually returned to service: USS ''Nevada'', USS ''California'', USS ''Tennessee'', USS ''Maryland'', and USS ''West Virginia''. All were to fight again, but not as the core of a surface force, except at the [[Battle of Surigao Strait]] — more of an execution than a battle. For the limited surface gunfire actions between battleships in the Pacific, only later classes were to see action. Those ships were at anchor, and arguably less vulnerable than a maneuvering vessel at sea. Neverthless, three days later, the British battleship HMS ''Prince of Wales'' and battlecruiser HMS ''Repulse'' were sunk by Japanese aircraft. | ||

==Later classes== | ==Later classes== | ||

Revision as of 15:36, 26 December 2012

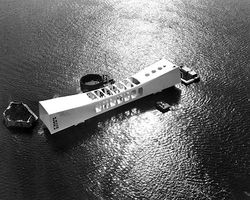

The USS Arizona memorial in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii which spans over the wreckage of the battleship.

The battleship, though now essentially obsolete as a naval weapon, is a naval vessel intended to engage the most powerful warships of an opposing navy. Evolved from the ship of the line, their main armament consisted of multiple heavy cannon mounted in movable turrets. The ships boasted extensive armor and as such were designed to survive severe punishment inflicted upon them by other capital ships.

A general criterion (especially after the revolution of HMS Dreadnought) is that the armor of a true battleship must be sufficiently thick to withstand a hit by its own most powerful gun, under certain constraints. Battlecruisers, while having near-battleship-sized guns, did not meet this standard of protection, and instead were intended to be fast enough to outrun the more heavily armed and armored battleship.[1]

From 1905 to the early 1940s, battleships defined the strength of a first-class navy. The idea of a strong "fleet in being", backed by a major industrial infrastructure, was key to the thinking of the naval strategist per Alfred Thayer Mahan, writing in his 1890 book, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1763 (1890). The essence of Mahan from a naval viewpoint is that a great navy is a mark and prerequisite of national greatness. In a 1912 letter to the New York Times, he counseled against relying on international relations for peace, and pointed out that other major nations were all building battleships. [2]

Asymmetrical threats to battleships began, in the early 20th century, with torpedoes from fast attack craft and mines. These underwater threats could strike in more vulnerable spots than could heavy guns. Aircraft, however, became an even more decisive threat by World War II.

Pre-dreadnoughts

A depiction of the ironclad USS Monitor sinking in a storm off Cape Hatteras on the night of December 30-31, 1862.

Pre-dreadnoughts were steam-powered, usually coal-fueled, armored warships with a typical main battery of four heavy guns. They also had a secondary battery of large guns, plus a tertiary battery of medium guns for such purposes as defense against fast attack craft. Some have suggested that the USS Monitor might have been the prototype, but, while she had a single armored turret of heavy guns, she was so unseaworthy that she was limited to calm coastal (littoral) waters, and, outside the specialized environment of the American Civil War, had no power projection capability. Still, the Battle of Hampton Roads in 1862 arguably presaged later battleship duels. Even though a small number of such ships were under construction when HMS Dreadnought was launched, the emergence of this powerful class of warship immediately rendered the pre-dreadnoughts obsolete. A pre-dreadnought fighting a dreadnought could only engage with its heaviest guns, and the pre-dreadnoughts were also slow and unable to pursue weaker warships or commerce. They were scrapped, or assigned to missions such as coastal defense or shore bombardment.

Dreadnoughts

For a ship that only engaged an enemy vessel once (by ramming a German submarine), the HMS Dreadnought made every other battleship in existence, or under construction, obsolete. Admiral Jacky Fisher can fairly consider himself her father, insisting on the characteristics: guns of a single large caliber, in turrets, and high speed. Her large-caliber guns made irrelevant the intermediate-caliber guns of other ships as they could not get close enough to use them.

Armament

Main guns were typically 12"/300mm or larger in diameter and were meant for long-range engagements. Secondary batteries comprised of 9.2" or 8" guns, intended for use against smaller, lighter ships and at closer ranges.

Propulsion

2nd Class Battleship USS Maine (ACR-1) "anchored over her grave" in Havana Harbor on the afternoon of February 15, 1898, the date of her destruction.

Dreadnoughts were also oil- rather than coal-fueled. This was done for sound engineering reasons, but also would contribute to the role of the Middle East in world politics. Previously, a nation that wanted to have its warships operate worldwide needed a worldwide network of coaling stations on shore. Taking coal aboard was an exhausting, filthy operation for the crew and local labor, and still required shore security for the coaling stations. Warships had no effective mechanical aids to moving coal into their furnaces, so their crews required a large number of brawny stokers with shovels. Coal dust was not only dirty, but dangerous as well; coal dust in the air could explode, or break into spontaneous fire due to a buildup of static electricity. While the explosion that sank the pre-dreadnought USS Maine in 1898 (a major event which was attributed to a Spanish mine and consequently formed much of the pretext for the United States' involvement in the Spanish-American War) has never been definitively explained, most current thinking is that it was due to spontaneous combustion in the coal bunkers.[3][4]

Oil could be transferred from ship to ship by pumps, and refueling could take place in any port, or later, at sea. Oil could easily be pumped into the furnaces, obviating the need for stokers. Since the main source of oil was the Middle East, however, the needs of the Royal Navy would dominate British policy in that region: the source of oil had to be ensured. Jacky Fisher called himself an "oil maniac" as early as 1886, and Winston Churchill made oil propulsion a matter of national policy in 1911. Only oil could provide speeds of 25 knots or better, and Fisher and Churchill valued speed above armor. To implement this policy, Britain invested directly in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, acquiring" 51 percent of company stock, placed two directors on its board, and negotiated a secret contract to provide the Admiralty with a 20-year supply of oil under attractive terms."[5]

The underwater threat

Protection against fast attack craft remained an issue, even though the dominance of battleships was still trumpeted after the 1905 Battle of Port Arthur.[6] While the secondary or tertiary battery might be able to traverse as quickly as the same guns on what was first called a torpedo boat destroyer, then the modern destroyer, relatively slow-moving battleships might not be able to engage torpedo boats until they were dangerously close. Destroyers could provide a standoff screen. Japanese operations at Port Arthur were more complex than first realized. Under cover of the torpedo attacks, their vessels also laid mines; the Russian battleship Petropavlosk was to sink from striking one.

The first battleship sunk by a submarine, the German U-21, was HMS Triumph, in the Mediterranean on 15 June 1915. Two days later, the same submarine sunk HMS Majestic, [7] Underwater survivability was addressed after the Battle of Jutland, when Britain began to retrofit battleships with "blisters," or underwater bulges that a mine or torpedo could strike without penetrating to the inner hull.

Torpedo development continued, however, with a focus on lethality. The U.S. began the Second World War with a submarine torpedo that used a magnetic influence fuse intended to detonate under the most vulnerable part of targets, the keel. These torpedoes, however, were inadequately tested and simply did not work until the operational fleet began to analyze them and find a temporary fix. Few things were as frustrating to a submarine captain, executing a careful and stealthy approach, to fire and hear only a clunk as the torpedo hit the target and failed to explode. Japanese Type 93 "Long Lance" torpedoes, while not as ambitious in their fusing, were unprecedented, in WWII, in their range and warhead size.

The Diversion of the Battlecruiser

HMS Hood, the largest battlecruiser ever built, at anchor on March 17, 1924.

USS Missouri (BB-63) (the largest ship) and USS Alaska (CB-1) (on the other side of the pier)tied up at Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia circa August 1944.[8]

A less successful creation of Fisher, the idea of the battlecruiser was a vessel with battleship-caliber guns, very high speed, and reduced armor, so it could kill whatever it could catch and run away from whatever could kill it. Unfortunately, those large guns were seductive to battleship admirals, and, rather than using it as a cruiser killer and commerce raider, succumbed to the temptation of adding battlecruiser firepower to a battleship engagement.

As Admiral Sir David Beatty, commanding the battlecruisers at the Battle of Jutland observed as the second of his battlecruisers exploded and sank, "there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today." This should not have been a mystery: the "something" was inadequate doctrine for their use and inadequate armor for the role in which they were placed. David Hurst calls it bad management, not bad luck.[9]

Especially after Jutland, battlecruisers were in search of a mission. Few were built. The German WWII battlecruisers DKM Scharnhorst and DKM Gneisenau had some success as commerce raiders, but Scharnhorst died in battle against a true battleship, HMS Duke of York. HMS Hood also sank in a surface gunfire action, in 1940, fighting the battleship Bismarck and the cruiser Prinz Eugen; the shell that caused Hood to explode, however, is believed to have come from Prinz Eugen.

Some ships, such as the USS Alaska and Guam, were "large cruisers," and even more in search of a mission; they were less heavily gunned than battlecruisers.

The "pocket battleship," such as DKM Graf Spee, was really a media term; she was lighter than a battlecruiser and, for a time, an effective commerce raider. She was mission-killed by two light cruisers and a heavy cruiser at the Battle of the River Plate. Her main battery was 11", while true battleships had at least 12".

Treaty battleships

U.S.S. Massachusetts (BB-59) underway at 15 knots off Point Wilson, Washington on July 11, 1944.[10]

In an attempt to avoid a naval arms race, the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 both limited the maximum power of battleships to 16" guns and 35,000 ton displacement, and called for reductions in the naval forces of the United Kingdom, United States, and Japan, resulting in a tonnage ratio of 5:5:3. [11] An argument for the lesser Japanese tonnage was that it would operate in the Pacific only, while the U.S. and U.K. had two-ocean responsibilities. The conference, however, did not rigorously define any ship type other than heavy cruiser.

Some battlecruisers, under construction at the time of the Washington Naval Treaty, would have had to be scrapped if continued, so were converted to aircraft carriers; this was the origin of the U.S. Lexington-class.

Aircraft versus battleships

As aircraft developed after the First World War, air power advocates, notably Billy Mitchell of the U.S. Army Air Corps, claimed they had made battleships obsolete. In 1921, Mitchell led an experiment in bombing captured German battleships, culminated by the sinking of the Ostfriesland. [12] There were several attacks, with increasingly heavy bombs, on the target ships, with inspections afterward. Mitchell had defied the conventional wisdom by ordering his aviators to try to drop the bombs in the water near the ships, rather than on them, in order to maximize the water-conducted shock wave. 600-pound bombs mission-killed the dreadnought and might have sunk her had damage control been inadequate, but the 2,000 pound bombs, on the next day, sunk her in under an hour. While Mitchell was technically correct, his shrill approach led to his court-martial, and interfered with his mission. Whether it was Mitchell's poor communications, or conservatism of the battleship admirals, most nations went into the Second World War assuming the battleship could defend itself against the stings of virtual insects.

One of the failures of U.S. preparation for the Battle of Pearl Harbor was an assumption that aircraft could not deliver torpedoes, the most powerful weapon against armored ships, in the shallow waters of the harbor. On the night of 11-12 November 1940, British carrier-based torpedo aircraft attacked the Italian fleet at the Battle of Taranto. Three battleships were hit and disabled, with two out of service until mid-1941 and the Conte di Cavour never repaired. In their planning, the Japanese were very aware of the capabilities demonstrated at Taranto.[13]

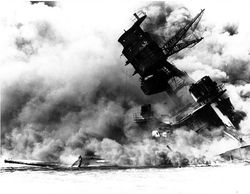

At the Battle of Pearl Harbor, USS Arizona exploded and settled to the bottom, her superstructure partially above the shallow water; her wreck is now a memorial. The exceptional violence of the explosion has never been definitively explained. It was caused by one or more bombs from high-level bombers. "...since the bomb apparently did not pierce Arizona's armored deck, which protected her magazines. Many qualified authorities have blamed powder storage outside of the magazines as the cause, but this is conjectural and probably will always remain so. In any case, the battleship was utterly devastated from in front of her first turret back into her machinery spaces. Her sides were blown out and the turrets, conning tower, and much of the superstructure dropped several feet into her wrecked hull. This tipped her foremast forward, giving the wreck its distinctive appearance."[14]

The USS Oklahoma later sank while being salvaged. All the other battleships at Pearl Harbor were damaged, but eventually returned to service: USS Nevada, USS California, USS Tennessee, USS Maryland, and USS West Virginia. All were to fight again, but not as the core of a surface force, except at the Battle of Surigao Strait — more of an execution than a battle. For the limited surface gunfire actions between battleships in the Pacific, only later classes were to see action. Those ships were at anchor, and arguably less vulnerable than a maneuvering vessel at sea. Neverthless, three days later, the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse were sunk by Japanese aircraft.

Later classes

Interwar designs such as the U.S. North Carolina and South Dakota-classes or German Bismarck-class had 15"-16" main batteries, secondary batteries usually in the 4"-6" range, and increasing number of antiaircraft autocannon. The final battleships of the Yamato-class had 18.1" guns, although their performance, in some respects, was inferior to the smaller-bore guns of the Iowa-class.

Different countries chose different optimizations. While German battleships were fully seaworthy, their planned missions would be relatively short, as opposed to British and American vessels that might need to fight worldwide. The German ships, therefore, did not emphasize crew habitability; when faced with design choices between survivability and habitability, they would take the most survivable approach, such as smaller compartments with more watertight hatches. DKM Bismarck took incredible punishment, but her actual sinking seems to have been a mixture of scuttling and torpedo hits.

U.S. vessels went further than the British both in habitability and damage control. Since the Great White Fleet circled the globe in 1909, self-sufficiency in global operations was a major U.S. goal. Britain still had worldwide scope, but also had a network of naval bases that the U.S. did not. In designing the Iowa-class in 1936, the U.S. did not have accurate details of the main armament of the Yamato and Bismarck-classes, but went through extensive design tradeoffs before selecting the 16"-50 caliber MK 7 naval guns over the 16"-45 caliber MK 6 of the North Carolina and South Dakota-classes.

The final duels

While it did not involve the most advanced battleships of the US or Japan, the Battle of Surigao Strait was the last engagement involving battleships on both sides, which actually fired at one another. Even though there was battleship gunnery, however, much of the damage to the Japanese battleships was done by torpedoes.

The last gunfire-only engagement involving a battleship put the HMS Duke of York against the German battlecruiser DKM Scharnhorst in the Battle of the North Cape, 26 December 1943. Scharnhorst sank, with 1,932 men lost and 36 survivors. The last true battleship-vs-battleship duel, with some cruiser and destroyer help, was USS Washington sinking IJN Kirishima during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal.

In the Mediterranean, when the Italian fleet tried to join the Allies, the battleship RN Roma was sunk by a German Fritz-X air-to-surface missile.[15]

Battleships' roles increasingly became shore bombardment, of questionable effectiveness, and antiaircraft protection of carriers, where they were more formidable.

Last of the giants

A few naval theorists suggest the exceptionally fast U.S. Iowa-class battleships of World War II were really battlecruisers. Indeed, they were faster than the previous true South Dakota-class battleships and the planned Montana-class giants, but they had excellent armor. While their main guns were 16" rather than the 18.1" of the largest Japanese Yamato-class battleships, their speed, fire control, and probably better-penetrating ammunition might well have led them to defeat Yamato and Musashi, if the aviators had not sunk them first.

Ironically, the only shots the Yamato fired in anger were against aircraft, at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, where her sister, Musashi, was sunk by aircraft alone. [16] Had Yamato's fleet commander persevered, however, in the Action off Samar, her guns indeed could have been devastating against transports and amphibious ships, lightly guarded off the invasion beach.

The Montana-class battleships, which would have had 12-16" guns versus the 9 on the Iowas, better armor, but slower speed, were cancelled in 1942 before any went into construction. The last battleship actually built, commissioned in 1946, was the British HMS Vanguard. Japan formally surrendered to the Allies on the deck of the USS Missouri. As well as ending a war, that act may have symbolized the loss of the primacy of the battleship — as hundreds of carrier-launched aircraft flew in salute overhead.

Shore bombardment

WWII U.S. and British battleships were fairly useful in naval gunfire support (NGFS), and U.S. battleships continued this role into the Gulf War. By the Vietnam War, the light antiaircraft batteries of the remaining battleships were removed as irrelevant against modern threats. The 5" secondary batteries, however, remained useful for NGFS.

There was considerable argument, however, that the remaining 16"/406mm battleship main gun was not as useful, for NGFS, as modern 8"/203mm guns of heavy cruisers. The 16" guns were slower-firing, were not as accurate so could not be used as close to friendly troops, and had shells with warheads optimized for naval combat rather than shore bombardment.

Additions

The last remaining Iowa-class battleships were equipped with AGM-84 Harpoon anti-shipping missiles and BGM-109 Tomahawk land attack cruise missiles. They had to be mounted in armored box launchers, which had much lower density than the vertical launch system of Burke-class destroyers and Ticonderoga-class cruisers, for the blast of 16" guns would otherwise damage the missile launchers. 16" muzzle blast and vibration remained a serious problem for modern electronics.

USS Missouri (BB-63), after launching Tomahawks, provided NGFS at the Battle of Khafji, and as part of a fake amphibious landing against Kuwait. [17] While the accompanying British frigate, HMS Gloucester, used Sea Dart missiles to shoot down a Silkworm anti-shipping missile aimed at a U.S. battleship in the Gulf War, the battleships did have Phalanx close-in weapons systems for final protective fire. Nevertheless, it is not a certainty that battleship armor would have protected all their systems against a modern missile strike, particularly since antennas cannot easily be armored.

A large Soviet anti-shipping missile, such as the Raduga KSR-5 (NATO: KINGFISH) or P-700 Granit (NATO: SHIPWRECK) had considerably more destructive power than the largest battleship shells, and even main armor might not have resisted them.

References

- ↑ Robert K. Massie (1992), Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the Coming of the Great War, Ballantine, ISBN 9780345375568

- ↑ Alfred Thayer Mahan (14 April 1912), "HOPELESSLY OUTFORCED."; Admiral Mahan Prophesies Plight of Nation Without More Battleships.", New York Times

- ↑ In later years, Admiral Hyman Rickover became interested in the explosion and reports of his subsequent investigations are generally accepted as factual.

- ↑ Hyman Rickover (1976), How the Battleship Maine was Destroyed, U.S. Department of the Navy

- ↑ Erik Dahl (Winter 2000-2001), "Naval Innovation: from Coal to Oil", Joint Forces Quarterly

- ↑ "BATTLESHIP SUPREME SAYS THE NAVAL BOARD; Torpedo Craft Generally Unsuccessful in Present War. NO TEST FOR THE CRUISERS Statement Relates That the 24 Russian Destroyers in Port Arthur Did Not Score a Hit", New York Times, 4 January 1905

- ↑ Story of the U-21, National Underwater and Marine Agency

- ↑ Also seen are the escort carrier USS Croatan (CVE-25) and destroyers of the Fletcher and "Four-Pipe, Flush-Deck" destroyer classes at the next pier.

- ↑ David K. Hurst, Bloody Ships

- ↑ "Big Mamie" fired the first and last American 16" projectiles "in anger" during the Second World War (these being at the November 8, 1942 Naval Battle of Casablanca and in the form of shore bombardment against the Japanese city of Kamaishi on August 9, 1945.

- ↑ Norman Friedman, U.S. battleships: an illustrated design history, U.S. Naval Institute

- ↑ "2,000-POUND BOMBS FROM ARMY PLANES SINK OSTFRIESLAND; "The Bombs That Sank Her Will Be Heard Bound the World," Says General Williams. IS BATTLESHIP OBSOLETE? Observers Answer No, but New Means of Protection Must Be Created. TWO BOMBS DID THE WORK Dropped in the Sea Near the Ship, They Opened Her Seams and Sank Her in 25 Minutes", New York Times, 22 July 1921

- ↑ Battles: Taranto 1940, Royal Navy

- ↑ Pearl Harbor Raid, 7 December 1941: USS Arizona during the Pearl Harbor Attack, U.S. Naval Historical Center

- ↑ Cestra, Francesco, The Sinking of the Battleship Roma, September 9th, 1943

- ↑ Yamato (Battleship, 1941-1945) -- in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, 22-26 October 1944, U.S. Naval Historical Center

- ↑ , Missouri, Dictionary of American Fighting Ships, U.S. Naval Historical Center