Quantum computation: Difference between revisions

imported>Charles Blackham mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Throughout this article | {{subpages}} | ||

Throughout this article the [[Many Worlds Interpretation]] (MWI) of [[quantum mechanics]] is used. | |||

==Differences with classical computation== | ==Differences with classical computation== | ||

In [[ | In [[classical computation]] there is the concept of a discrete [[bit]], taking only one of two values. However , the world which [[classical physics]] describes is that of continua. Thus this is obviously not an ideal way of attempting to describe or simulate the world in which we live. [[Richard Feynman|Feynman]] was the first to consider the idea of a quantum computer being necessary to simulate the quantum mechanical world in which we live.<ref>R.P. Feynman ''International Journal of Theoretical Physics 21(6/7) 1982''</ref> | ||

==Quantum computers | ==Quantum computers and information theory== | ||

The quantum mechanical analogue of the [[Bit|classical bit]] is the qubit. A qubit is an actual physical system, all of whose [[Observable (quantum computation)|observables]] are Boolean. | The quantum mechanical analogue of the [[Bit|classical bit]] is the qubit. A qubit is an actual physical system, all of whose [[Observable (quantum computation)|observables]] are Boolean. | ||

==Interference & a simple computation== | ==Interference & a simple computation== | ||

==Quantum | ==Quantum algorithms== | ||

An algorithm is a '''hardware- | An algorithm is a '''hardware-independent''' recipe for performing a particular computation. A program is a way of preparing a specific computer to do such a task. Algorithms for quantum computers offer a wider range of computational tasks which may be solved by the use of interference. Some of the new possibilities which are opened up may prove to have drastic consequences for the future: e.g. Shor's algorithm relevance to cryptography. | ||

===Oracles=== | ===Oracles=== | ||

An oracle is a black box which it is impossible to look inside and performs a particular function ''f'' on the input qubits in a time which is | An oracle is a black box which it is impossible to look inside and performs a particular function ''f'' on the input qubits in a time which is independent of the particular input. It is not possible. | ||

They are used to simplify the analysis of algorithms as the specific nature of how a task is performed is irrelevant due to the criterion of hardware- | They are used to simplify the analysis of algorithms as the specific nature of how a task is performed is irrelevant due to the criterion of hardware-independence. The oracle must of course be reversible as the laws of QM do not make a distinction between forwards and backwards time (i.e. time does not have 'an arrow').<br/> | ||

===Dynamics of quantum gates in Schrödinger picture=== | ===Dynamics of quantum gates in Schrödinger picture=== | ||

| Line 42: | Line 44: | ||

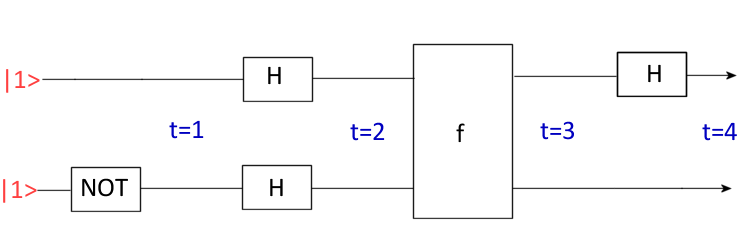

===Deutsch algorithm=== | ===Deutsch algorithm=== | ||

Let us create an oracle which performs the following function: <math>f: \{-1,1\} \mapsto \{-1,1\}</math><br/> | Let us create an oracle which performs the following function: <math>f: \{-1,1\} \mapsto \{-1,1\}</math><br/> | ||

There are four | There are four possibilities for this function:<br/> | ||

# identity: <math>x \mapsto x</math> | # identity: <math>x \mapsto x</math> | ||

# not: <math>x \mapsto -x</math> | # not: <math>x \mapsto -x</math> | ||

| Line 49: | Line 51: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

Computational task: To determine if <math>f(1)=f(-1)</math>.<br/> | Computational task: To determine if <math>f(1)=f(-1)</math>.<br/> | ||

This is | This is equivalent to trying to determine <math>f(1)f(-1)</math> without looking inside the oracle above. | ||

Classically this may be done by consulting the oracle twice. '''[diagram of classical situation]''' However, using quantum computation the oracle need only be consulted once.<br/> | Classically this may be done by consulting the oracle twice. '''[diagram of classical situation]''' However, using quantum computation the oracle need only be consulted once.<br/> | ||

| Line 64: | Line 66: | ||

<math>\left | \psi(3) \right \rangle = \frac{1}{2}(\left | 1,f(1) \right \rangle + \left | -1,f(1) \right \rangle - \left | 1,-f(-1) \right \rangle - \left | -1,-f(-1) \right \rangle)</math><br/> | <math>\left | \psi(3) \right \rangle = \frac{1}{2}(\left | 1,f(1) \right \rangle + \left | -1,f(1) \right \rangle - \left | 1,-f(-1) \right \rangle - \left | -1,-f(-1) \right \rangle)</math><br/> | ||

Now we must examine the two | Now we must examine the two possibilities 1) <math>f(1)=f(-1)</math> and 2) <math>f(1)=-f(-1)</math><br/> | ||

1. Let <math>f(1)=f(-1)=f</math><br/> | 1. Let <math>f(1)=f(-1)=f</math><br/> | ||

<math>\Rightarrow \left | \psi(3) \right \rangle = \frac{1}{2}(\left | 1,f \right \rangle + \left | -1,f \right \rangle - \left | 1,-f \right \rangle - \left | -1,-f \right \rangle) | <math>\Rightarrow \left | \psi(3) \right \rangle = \frac{1}{2}(\left | 1,f \right \rangle + \left | -1,f \right \rangle - \left | 1,-f \right \rangle - \left | -1,-f \right \rangle) | ||

| Line 71: | Line 73: | ||

<math>\Rightarrow \left | \psi(3) \right \rangle = \frac{1}{2}(\left | 1 \right \rangle - \left | -1 \right \rangle)(\left | f \right \rangle - \left | -f \right \rangle)</math><br/> | <math>\Rightarrow \left | \psi(3) \right \rangle = \frac{1}{2}(\left | 1 \right \rangle - \left | -1 \right \rangle)(\left | f \right \rangle - \left | -f \right \rangle)</math><br/> | ||

In each of these cases the state vector when t=3 is a superposition of two [[Pure state|pure states]]: <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left | 1 \right \rangle \pm \left | -1 \right \rangle)</math> and <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left | f \right \rangle \pm \left | -f \right \rangle)</math>. The purpose of the final Hadamard gate is to | In each of these cases the state vector when t=3 is a superposition of two [[Pure state|pure states]]: <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left | 1 \right \rangle \pm \left | -1 \right \rangle)</math> and <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left | f \right \rangle \pm \left | -f \right \rangle)</math>. The purpose of the final Hadamard gate is to differentiate between the states <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left | 1 \right \rangle \pm \left | -1 \right \rangle)</math> and thus determine whether <math>f(1)=f(-1)</math> or not.<br/> | ||

<math>H\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left | 1 \right \rangle + \left | -1 \right \rangle)= \left | 1 \right \rangle</math><br/> | <math>H\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left | 1 \right \rangle + \left | -1 \right \rangle)= \left | 1 \right \rangle</math><br/> | ||

| Line 81: | Line 83: | ||

===Shor's algorithm=== | ===Shor's algorithm=== | ||

Shor's algorithm is used to find the factors of a number. It is particularly important because of the use in cryptography of multiplying together two large prime numbers. Factoring this number into its prime factors allows the cracking of the code. | |||

The algorithm itself has two parts: one quantum and one classical. The latter can be done in <math>O(x^n)</math> time. The use of a quantum algorithm makes this true for the former part as well. | |||

Let us wish to factor a number ''n''. | |||

The first part of the algorithm wishes to find the period, ''r'', of the function: | |||

:<math>\scriptstyle F(a)=x^a \pmod n</math>, i.e. find <math>r</math> such that <math>\scriptstyle F(a)=F(a+r)\,</math> | |||

Once <math>r</math> has been found by use of quantum parallelism, the second part of the algorithm may be performed: | |||

: <math>x^0 \pmod n=1</math> | |||

: <math>\Rightarrow x^r mod\,n=1, x^{2r} \pmod n=1</math> etc. | |||

: <math>\Rightarrow x^r \equiv 1 \pmod n</math> | |||

: <math>\Rightarrow (x^{\frac{r}{2}})^2 = x^r \equiv 1 \pmod n</math> | |||

: <math>\Rightarrow (x^{\frac{r}{2}})^2 - 1 \equiv 0 \pmod n</math> | |||

: <math>\Rightarrow (x^{\frac{r}{2}} - 1)(x^{\frac{r}{2}} + 1) \equiv 0 \pmod n</math> if <math>r</math> is even. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 87: | Line 111: | ||

# ''[http://cam.qubit.org/ Cambridge Centre for Quantum Computation]'' | # ''[http://cam.qubit.org/ Cambridge Centre for Quantum Computation]'' | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<references/> | <references/>[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | ||

[[Category: | |||

Latest revision as of 06:00, 9 October 2024

Throughout this article the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics is used.

Differences with classical computation

In classical computation there is the concept of a discrete bit, taking only one of two values. However , the world which classical physics describes is that of continua. Thus this is obviously not an ideal way of attempting to describe or simulate the world in which we live. Feynman was the first to consider the idea of a quantum computer being necessary to simulate the quantum mechanical world in which we live.[1]

Quantum computers and information theory

The quantum mechanical analogue of the classical bit is the qubit. A qubit is an actual physical system, all of whose observables are Boolean.

Interference & a simple computation

Quantum algorithms

An algorithm is a hardware-independent recipe for performing a particular computation. A program is a way of preparing a specific computer to do such a task. Algorithms for quantum computers offer a wider range of computational tasks which may be solved by the use of interference. Some of the new possibilities which are opened up may prove to have drastic consequences for the future: e.g. Shor's algorithm relevance to cryptography.

Oracles

An oracle is a black box which it is impossible to look inside and performs a particular function f on the input qubits in a time which is independent of the particular input. It is not possible.

They are used to simplify the analysis of algorithms as the specific nature of how a task is performed is irrelevant due to the criterion of hardware-independence. The oracle must of course be reversible as the laws of QM do not make a distinction between forwards and backwards time (i.e. time does not have 'an arrow').

Dynamics of quantum gates in Schrödinger picture

NB In the Schrödinger picture the state vector evolves in the following manner:

where is the characteristic unitary matrix of the gate.

NOT

So if then

Controlled Not, CNOT

This i a two input gate where whether the NOT operation is performed on the second is dependant (i.e. controlled) by the value of the first input bit which is unchanged.

Hadamard gate, H

The Hadamard gate, normally denoted as H, creates an equally weighted superposition of the and states. There is no classical analogue of it.

i.e the Hadamard gate is self-inverse.

Oracle

An oracle which performs the function has the following dynamics in the Schrödinger picture. The value of y is normally set to one so that the output is and .

Deutsch algorithm

Let us create an oracle which performs the following function:

There are four possibilities for this function:

- identity:

- not:

- output -1:

- output 1:

Computational task: To determine if .

This is equivalent to trying to determine without looking inside the oracle above.

Classically this may be done by consulting the oracle twice. [diagram of classical situation] However, using quantum computation the oracle need only be consulted once.

(N.B. For the analysis of algorithms, the Schrödinger picture is often preferable and thus shall be used here. It is of course still possible to use the Heisenberg picture.

Now we must examine the two possibilities 1) and 2)

1. Let

2. Let

In each of these cases the state vector when t=3 is a superposition of two pure states: and . The purpose of the final Hadamard gate is to differentiate between the states and thus determine whether or not.

Thus

Grover's algorithm

Shor's algorithm

Shor's algorithm is used to find the factors of a number. It is particularly important because of the use in cryptography of multiplying together two large prime numbers. Factoring this number into its prime factors allows the cracking of the code.

The algorithm itself has two parts: one quantum and one classical. The latter can be done in time. The use of a quantum algorithm makes this true for the former part as well.

Let us wish to factor a number n. The first part of the algorithm wishes to find the period, r, of the function:

- , i.e. find such that

Once has been found by use of quantum parallelism, the second part of the algorithm may be performed:

- etc.

- if is even.

References

Based on a talk given by Charles Blackham to 6P at Winchester College, UK on 7/3/07

- Lectures on Quantum Computation by David Deutsch

- Cambridge Centre for Quantum Computation

- ↑ R.P. Feynman International Journal of Theoretical Physics 21(6/7) 1982